Protocol Review 5: Gossip

Gossip as Protocol: A Comparative Casebook on Village Gossip, Distributed Gossip Protocols, and Community Notes

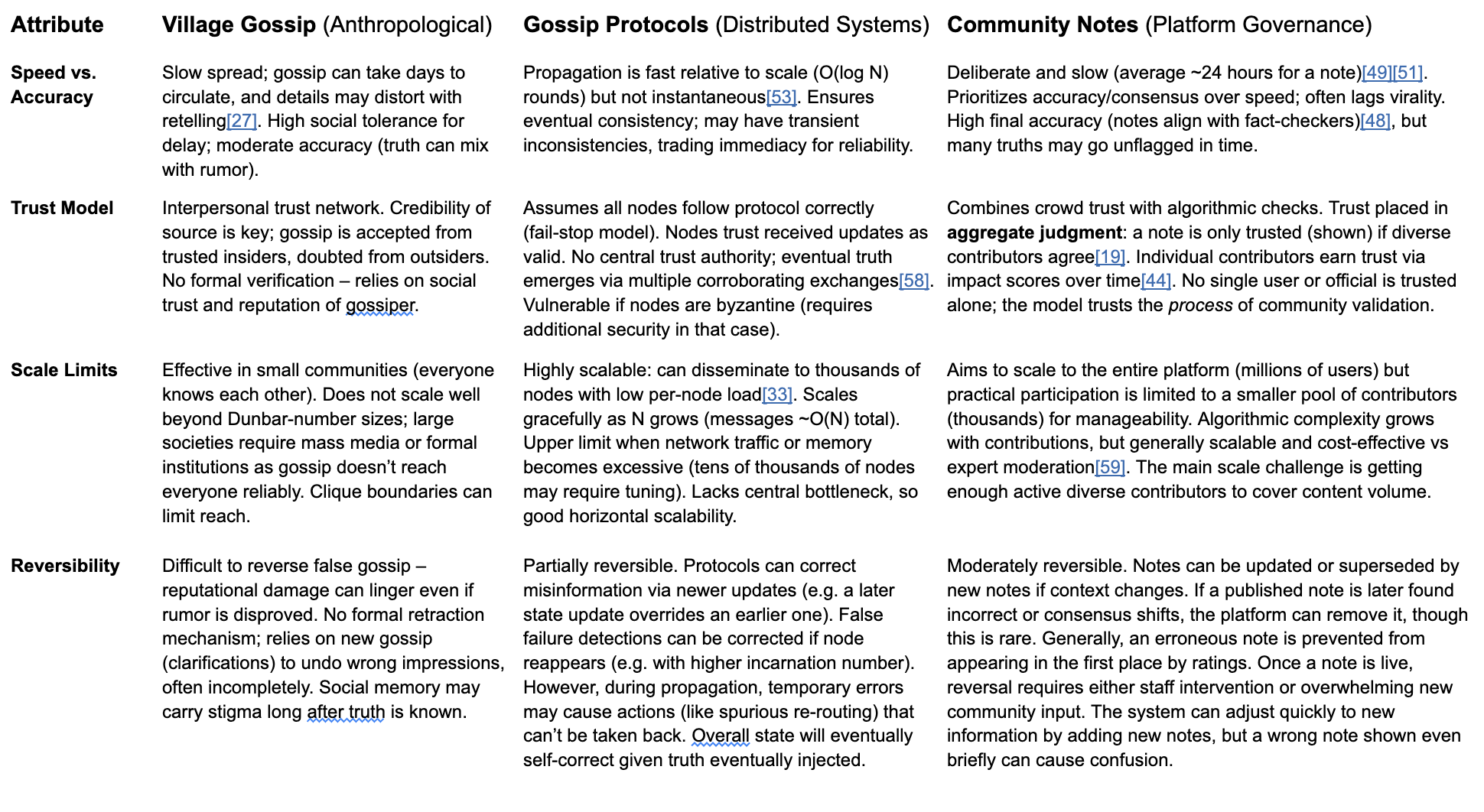

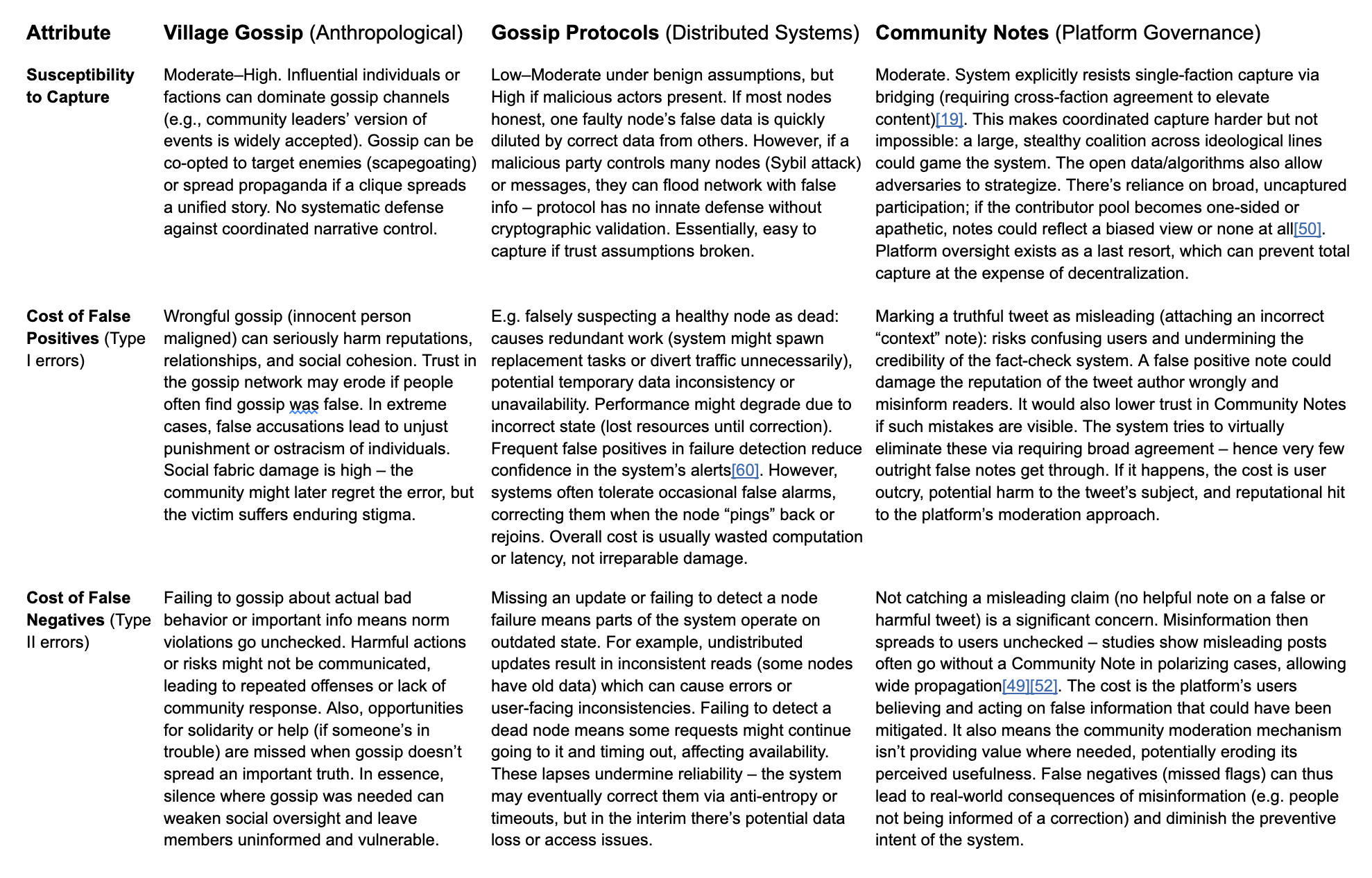

This report presents a procedural analysis of gossip as a decentralized coordination protocol across three domains: anthropological village gossip, distributed systems gossip protocols, and Twitter’s Community Notes. Each system is examined through a uniform schema: actors and roles, message formats, admission rules, incentives, state transitions, error handling, and failure modes. Drawing from canonical sources (Gluckman, Bergmann, Goffman), technical specifications (Demers et al., SWIM), and platform governance documentation (Yondon Fu, Twitter), the report treats gossip as protocol: a system for probabilistic adjudication under conditions of partial information and no sovereign authority. Structural isomorphism across cases allows for direct comparison, summarized in a table. The report concludes with speculative futures in AI-agent ecosystems, federated networks, and adversarial information environments. Findings emphasize that while gossip systems are resilient and scalable, their failure modes intensify under epistemic fragmentation, anonymity, and loss of shared context.

1. Definition and History of Gossip as Protocol

Gossip can be defined in structural terms as a decentralized mechanism for circulating information and enforcing group norms, operating without a central authority. Anthropologists like Max Gluckman observed that in small communities, gossip follows customary rules and serves positive social functions: it upholds group unity, moral standards, and regulates competition for status[1]. Rather than idle chatter, gossip in traditional societies is “part of the very blood and tissue” of community life[2][3]. Jörg Bergmann’s sociological analysis further formalized gossip’s structure: it is a triadic communication involving an absent subject (the person being discussed), a gossip transmitter who shares sensitive information about that subject, and a gossip recipient who knows the subject and contributes to the exchange[4][5]. Crucially, gossip is “news about the personal affairs of another” conveyed in a particular interactive style[6]. Erving Goffman’s work on social interaction provides context for gossip’s role in adjudicating personal reputation: gossip moves hidden “backstage” behaviors into the “front stage,” effectively exposing private conduct to public awareness[7]. In sum, classical scholarship treats gossip as an informal adjudication system for social conduct, one that disseminates reputational information and collectively arbitrates acceptable behavior.

Technologists later adopted the term “gossip protocol” to describe analogous processes in distributed computer systems[8]. In 1987, Demers et al. introduced epidemic algorithms for distributed databases, explicitly modeling data propagation on the pattern of rumor spreading[9][10]. A gossip protocol in computing is a peer-to-peer procedure where each node periodically selects another at random to exchange state information, much as office workers might randomly share the latest rumor at the water cooler[11][12]. Over many such interactions, information “infects” the network, eventually reaching all nodes without centralized coordination[8]. These protocols coordinate updates and consensus in a decentralized manner, leveraging redundancy and probabilistic propagation to achieve robust convergence[13][14]. For example, the SWIM membership protocol (2002) and its implementations (like HashiCorp’s Memberlist) use gossip to disseminate node liveness information and group membership changes in large clusters[15][16]. The conceptual lineage is direct: what anthropology saw as a pervasive pattern of human coordination, computer science re-purposed as an algorithmic pattern for fault-tolerant distributed systems.

In recent years, platform governance has explored gossip-like community moderation systems. Twitter’s Community Notes (formerly Birdwatch), launched in 2021, is a large-scale attempt to harness crowd-based judgment to identify misleading content[17][18]. Instead of top-down moderation, Community Notes invites a broad network of users (Contributors) to attach factual context notes to posts and rate each other’s notes. A note is only published as “Helpful” if a diverse subset of contributors (often with opposing viewpoints) converges in rating it positively[19]. This approach mirrors gossip’s decentralized adjudication: many independent actors share and vet information until a consensus emerges about what interpretation should be publicly shown. In structural terms, Community Notes functions as a protocol for crowdsourced content adjudication, relying on the “collective judgment of users” rather than any single editor[20][21]. The following sections present three detailed case specifications – Village Gossip, Technical Gossip Protocols, and Community Notes – using a parallel schema to facilitate direct comparison.

2. Three Case Specifications

2.1 Village Gossip (Anthropological Case)

Actors / Roles: Village gossip involves a network of community members who take on recurring roles in gossip exchanges. A typical gossip triad includes: (a) the subject – an absent third person (often an adult community member) whose private conduct or reputation is under discussion[4]; (b) the gossip initiator or “producer” – a member who knows of some event or secret and transmits this information to others[22]; and (c) the gossip recipients – one or more peers who listen and actively respond, often already acquainted with the subject[5]. All participants are usually insiders to the community or subgroup, sharing some social ties. There is no official leader of a gossip network; influence depends on trust and social status. Elderly or central figures may act as key gossip hubs, but they remain peers rather than authorities in the process. The subject of gossip is not present to defend themselves, which is essential to the gossip dynamic. Overall, gossip’s actors are informal equals, and any member in good standing can play transmitter or receiver – though as noted below, not everyone is immediately admitted into gossip circles.

Message Format: The content of village gossip is typically an anecdotal narrative or report about the subject’s personal affairs or behavior[6]. It may describe a deviation from social norms, a scandal, or any notable private incident. The message format is informal and oral, often relayed in a conversational tone. Gossip communication is highly contextual: the gossiper often couches the information with moral commentary or dramatic flair to engage the listener. Importantly, gossip information is considered semi-confidential: it is shared discreetly, in trusted subgroups, even as it breaches the subject’s privacy (hence Bergmann’s term “discreet indiscretion” for gossip)[23]. The typical gossip message includes an implicit judgment – approval or disapproval – guiding the listener on how to view the subject in light of the revealed information. As an unwritten protocol, gossip uses devices like lowering the voice, checking that the subject is absent, and sometimes invoking phrases (“just between us…”) to signal that a gossip mode is in effect. The data structure here is narrative: often a story or allegation that can evolve as it passes from person to person.

Admission Rules: Informal social rules govern who can participate in gossip and under what conditions. Gossip is generally restricted to in-group members who have earned trust. Newcomers or outsiders are initially excluded from sensitive gossip until they are vetted by the community. For instance, Gluckman observes that in tightly-knit villages, trespassing the customary rules of gossip is heavily sanctioned[1]. One must know whom one can tell what – sharing a scandal with the wrong audience (for example, a junior person gossiping publicly about a high-status elder) violates social protocol. Often gossip flows along existing relationship lines: close friends gossip freely with each other, whereas a known gossipmonger might be shunned if they indiscriminately spread stories. In many cultures, there are also genre rules: gossip about certain topics (family matters, sexual liaisons, etc.) may only be shared among same-gender or same-age peers. Fictional accounts echo these rules; for example, in Jane Austen’s Emma (noted by Gluckman), a newcomer’s attempt to join the village’s elite gossip too quickly is rebuffed, illustrating that “the right to gossip idly was severely restricted” to established insiders[24]. In summary, entry to gossip networks requires social authentication – one must be recognized as a bona fide community member and a trustworthy confidant.

Incentives: The gossip protocol in villages is driven by both social and normative incentives. On a social level, engaging in gossip builds bonds and alliances – sharing a juicy story signals trust (the gossiper trusts the listener not to betray them) and creates a sense of intimacy or camaraderie. Participants gain reputational capital by demonstrating that they are “in the know.” On a normative level, gossip incentivizes conformity: it is a key mechanism of social control. When someone misbehaves, the fear of becoming “talk of the town” deters rule-breaking. Gossip thus enforces norms by exposing and sanctioning deviance in the court of public opinion[25]. The community is incentivized to engage in gossip because it helps maintain shared values and unity[26]. Furthermore, gossip can serve individual strategic interests – e.g. undermining a rival’s reputation – but these selfish uses are tempered by the risk: a malicious gossiper can themselves become a target if others perceive them as spreading false or excessive scandal. In short, the incentive structure balances collective benefit (norm reinforcement, group cohesion) with personal benefits (entertainment, alliance formation) under an overarching principle that gossip should ultimately affirm the community’s value system[26].

State Transitions: In the village gossip system, the implicit “state” being managed is the reputation state of community members and the consensus about events. A person’s standing (honorable, suspect, disgraced, etc.) shifts as gossip about them spreads and is believed. For example, an initial report (state: only a few know) might escalate to wide awareness (state: everyone “has heard”) if it continues to circulate. As gossip travels, stories may be embellished or modified, causing the shared narrative to transition with each retelling[27]. There is no centralized record; the “state” resides in communal memory and ongoing conversations. However, one can speak of the community reaching a settled opinion (e.g. “it’s generally accepted that person X cheated in the trade”) – that is a convergent state achieved via gossip adjudication. Gossip interactions can also change relational states: two individuals who gossip together move to a closer trust state. If new evidence or a new gossip counters an earlier rumor, the community’s stance on the subject might transition again (though reversals are often slow and incomplete). Notably, gossip has a persistent effect: even after active gossip dies down, the reputational mark can persist in collective memory (“scarlet letter” effect). Thus, gossip serves as a state machine for social reputation – each gossip act triggers potential updates to who is respected, who is distrusted, and what narratives are dominant in the group.

Error Handling: The gossip process is inherently error-prone – false or exaggerated information can spread just as easily as truth. There are, however, informal correction mechanisms. Community members may cross-check stories with multiple sources (“Did you hear the same thing about X?”) and if discrepancies arise, gossip networks can adjust or discount unreliable information. If a subject convincingly refutes a rumor (for instance, proving an alibi for a scandalous accusation), that counter-story itself becomes gossip which can override the original tale. Gossipers who repeatedly relay false information suffer a loss of credibility, effectively penalizing unreliable nodes in the network – others may exclude them from future sensitive gossip. Culturally, there are also norms against certain kinds of gossip (e.g. unverified defamation or gossip that could seriously harm someone unjustly). If such lines are crossed, the community may sanction the gossiper (through social ostracism or reputational damage) as a form of error correction[1]. That said, these mechanisms are ad hoc. There is no formal retraction protocol; errors may never be fully purged. Often the best one can hope is that a false rumor “dies out” over time if people stop repeating it. In summary, error handling in village gossip relies on redundancy and reputation – multiple overlapping conversations eventually filter out egregious falsehoods, and those who propagate errors too often lose the trust required to be effective gossip participants.

Failure Modes: Several failure modes can undermine the gossip system. One is malicious gossip – if individuals intentionally spread slander to harm someone, gossip can become a tool of character assassination rather than norm enforcement. In extreme cases this leads to factionalism or scapegoating (e.g. baseless witch-hunt rumors that spiral out of control). Another failure mode is when the community’s shared context fragments: if the group splits into cliques that distrust each other, gossip may circulate only within echo chambers, failing to produce a community-wide consensus (different subgroups believe different versions of reality). Gossip also fails under conditions of authoritarian suppression – if an authority figure punishes any informal discussion, people self-censor and the gossip network collapses, removing a key feedback mechanism in the society. From the perspective of the protocol, gossip breaks down when trust is lost: either trust in the medium (everyone knows the grapevine is full of lies, so they stop listening), or trust between individuals (people fear to speak openly). High anonymity or population turnover can also cause failures, as gossip depends on recurring interactions; if people do not know each other or cannot attach rumors to known persons, the information has no social “hook” and dissipates. Lastly, gossip is vulnerable to context failure – if an event is widely misunderstood, gossip can reinforce the wrong interpretation (a collective misbelief) rather than correct it, essentially freezing the group in an erroneous state. In sum, gossip remains stable when there is a baseline of trust and shared norms; it breaks down or becomes harmful when exploited for aggressive ends or when the social fabric (the carrier of gossip) frays beyond a critical point.

2.2 Technical Gossip Protocols (Distributed Systems Case)

Actors / Roles: In a distributed gossip protocol, the actors are peer nodes (servers, processes, or agents) in a network. All nodes typically have equal roles in the protocol – there is no central coordinator or permanent leader. Each node acts both as a sender and receiver of gossip messages. For example, in a cluster using a gossip-based membership service, every server instance is a peer that can initiate a gossip exchange with others. The protocol design is usually symmetric: any node can gossip updates, detect failures, and propagate information. There may be transient roles during an interaction (one node plays the initiator of a gossip round, the other the target), but these roles are ephemeral and rotate randomly. Some implementations introduce minor role distinctions, such as a seed node that new nodes contact initially to join (essentially a known entry point), but after admission, the new node becomes an equal participant in gossip dissemination[16]. Overall, the actor model is a flat peer-to-peer topology – every node is both a client and server in gossip communication. The lack of hierarchy means the system’s reliability emerges from redundancy and collaboration among all nodes, rather than any specialized actor. This egalitarian structure mirrors the flat structure of village gossip (no single source of truth), transplanted into the realm of computing nodes.

Message Format: Gossip protocol messages in distributed systems are typically very structured and concise. A message often contains a small payload of state information plus metadata. For instance, in a membership gossip, the message might list a few tuples like (NodeID, Status, IncarnationNumber) indicating that Node X is alive or failed at a given logical time[15]. In a data gossip (rumor-mongering), the message could carry an update identifier or a digest of recent updates. A key property is that message size is bounded and fixed (or at least kept small) in each exchange[28]. Gossip protocols frequently use binary or ID-based formats rather than verbose text – e.g. a heartbeat message or a hash of data – to reduce overhead. The communication is often periodic and pairwise: Node A sends a “gossip packet” to Node B containing some state to merge; B may respond with its own state summary. Some protocols (like the SWIM membership protocol) separate message types for different purposes: a ping message (are you alive?), ack message (yes, I’m alive), ping-request (indirect check via third party), and membership update broadcast when a node is suspected or confirmed dead[29][30]. In summary, the message format is usually a compact, schema-defined data structure carrying either notifications (e.g. “X has failed” or “new data Y available”) or queries (“Are you alive?”). Unlike human gossip, computer gossip messages omit nuance and context – they are optimized for efficiency, containing only the necessary bits to update state machines on other nodes. The protocol ensures that over time, these small exchanges allow all nodes to converge on a common set of information.

Admission Rules: For a new node to join a gossip-based system, it must follow a defined bootstrap procedure. Typically, a joining node needs to know at least one current member’s address to introduce itself to the network[16]. For example, HashiCorp’s Memberlist (based on SWIM) requires a new node to contact a seed node; the seed then disseminates the newcomer’s presence to other peers as a membership update. Once introduced, the new node is added to everyone’s member lists and will be included in subsequent gossip rounds. There may be simple admission control checks, such as verifying the node’s protocol version or credentials if security is enabled, but classic gossip protocols often assume a cooperative environment (any node presenting the correct handshake can join). Some systems incorporate ACLs or authentication for gossip when used in untrusted settings, to prevent arbitrary nodes from joining and spamming. After admission, the node is treated like any other – it will start receiving gossip messages (like the full membership list or recent updates) to sync its state, and it will begin sending out gossip to others. In effect, the admission rule is one-time contact requirement: knowledge of at least one peer and adherence to protocol format. There is no central registry; the network relies on gossip to gradually spread the knowledge of the new node to all members[16]. In summary, joining a gossip network is decentralized and “viral” – a single introduction is sufficient to let the newcomer’s existence propagate through the cluster.

Incentives: Unlike human participants, computing nodes do not have independent motives; their “incentive” is programmed as system goals such as consistency and reliability. The design incentive of gossip protocols is to achieve eventual consistency of distributed state in a way that is scalable and fault-tolerant. Each node participates in gossip exchanges because the protocol ensures mutual benefit: by sharing information, all nodes move toward a synchronized state, which is necessary for correct operation (e.g. a distributed database needs all replicas to get updates). Thus, from a system perspective, gossip provides strong incentives in terms of robustness: the network can survive node failures and still disseminate data because gossip does not rely on any single link or server[31][32]. There is also an implicit incentive regarding resource usage – gossip protocols impose only modest, typically low-bandwidth communication per node, making them attractive for large systems[33]. Each node, by following the gossip algorithm, avoids the overhead of complex coordination (such as expensive consensus every time) while still obtaining a high probability that it will learn what it needs. In essence, the protocol’s incentive structure is cooperative: if all nodes gossip, the entire system’s data dissemination is reliable and fast; if a node were not to participate (withholding information or not forwarding updates), it would only isolate itself and risk having stale state. In sum, nodes are “incentivized” (via system design) to follow gossip behavior because it maximizes information availability and survivability for the cluster[34]. This mirrors how individuals in a village are socially incentivized to share gossip for group cohesion – here the “group” is a set of servers aiming for a coherent view of data.

State Transitions: In technical gossip, the state in question might be a membership list, a set of key-value updates, or any distributed data that needs synchronization. State transitions occur as nodes incorporate gossip information into their local state. For example, consider membership: a node’s state includes a list of known members and their status (alive/suspected/dead). When a gossip message arrives saying “Node Z failed,” the receiving node transitions Node Z’s status in its local list from alive to failed and then further gossips this update[15]. In a data store using gossip, a new data item or version update causes nodes that receive it to update their local copy (state change from old value to new value) and then carry the rumor forward. Gossip protocols often implement versioning or incarnation numbers to manage state transitions and resolve conflicts. For instance, each membership change can carry a counter; if a node receives conflicting gossip (one message says Node Z is alive with a higher incarnation vs another that Z is dead with an older incarnation), it will prefer the latest information – this ensures a consistent eventual state. The system’s overall state evolves incrementally and usually monotonically (e.g. once a node is marked failed and that info has highest version, that state persists unless a contradictory higher version appears, such as the node coming back with a new incarnation). These transitions propagate in a wave-like fashion: initially only one node’s state changes (when it detects an event or receives an update), then through gossip rounds many others change until convergence. Importantly, gossip protocols guarantee that given enough time and absent further changes, all correct nodes will converge to the same final state (e.g. everyone knows of a failure, or everyone has the latest data value) with high probability[35][14]. This eventual consistency is the key state convergence property of gossip. The state model is often probabilistic – there’s not a strict order of transitions, but mathematically the epidemic process has a high likelihood of infecting all nodes, driving the system from initial partial knowledge to globally consistent knowledge.

Error Handling: Robustness to errors (lost messages, transient misreads) is a hallmark of gossip protocols. Error handling is largely achieved through redundancy and probabilistic design rather than explicit detection of each error. If a gossip message is lost due to network issues, the protocol’s periodic retry nature means the information will likely reach the target through a different path or a later round (since multiple peers will independently gossip the update)[14]. For example, if Node A doesn’t hear about a new update because one exchange failed, Node B or C might pass that update to A in a subsequent cycle. In failure detection gossip (like SWIM), error handling includes indirect checks: if a direct ping to a node times out (which could be a false alarm due to network drop), the protocol has k other nodes each attempt to ping the target, reducing the chance of falsely declaring it dead[30][36]. This significantly lowers false positives in detecting failures by routing around network glitches[37]. Many gossip protocols also incorporate anti-entropy or periodic full sync rounds to correct any state divergence that lazy rumor-spreading might have missed[38][9]. In anti-entropy, a node will occasionally do a full database compare with a partner to resolve any differences, thereby catching errors from dropped updates at the cost of more bandwidth. If conflicting information circulates (e.g. two nodes have different versions of a value), gossip protocols may use techniques like version vectors or last-writer-wins policies to resolve the conflict once all info has propagated. Generally, no single failure or error stops the system; gossip is self-healing in that even if some messages are lost or some nodes crash, the rumor will continue to spread via other routes until consistency is reached[14]. The trade-off is that errors are not corrected immediately – there is a window of inconsistency – but given the protocol’s design, that window closes with high probability over time. Thus, error handling is achieved via eventual redundancy (multiple chances for delivery) and randomization (making it unlikely that the same link failure will consistently block an update).

Failure Modes: While resilient, gossip protocols have known failure modes, especially under extreme or adversarial conditions. One failure mode is network partition: if the network splits into disjoint subgroups (no gossip traffic between them), each subgroup will internally converge but the overall system becomes inconsistent (e.g. each partition thinks the other partition’s nodes are all failed). Gossip alone cannot heal a partition until connectivity is restored; when it is, the previously separated states might conflict. Another failure scenario is high churn or scale limits: gossip assumes a relatively stable membership during a gossip round. If nodes join and leave extremely rapidly or if the network size grows beyond the protocol’s tested limits, gossip may lag or saturate. For example, gossip message load is typically O(N log N) for N nodes to disseminate one update, which is scalable, but if N is in the tens of thousands and updates are continuous, network links could become congested. This can lead to increased propagation latency or, in worst cases, gossip collapse where messages queue up and state becomes stale. Additionally, classic gossip protocols often assume non-Byzantine failures (nodes may crash but not lie). Thus a critical failure mode is malicious nodes or data corruption: a compromised node could inject false gossip (e.g. claiming another healthy node is failed or spreading a fake update). Since gossip has no central authority, other nodes might accept and propagate this false information, causing a kind of “rumor virus.” Without additional safeguards (like cryptographic signatures or quorum verification), gossip networks are susceptible to coordinated attacks by multiple malicious nodes forging consistent lies. Another subtle failure mode is gossip convergence on a wrong value if initial data is wrong – gossip will happily spread a wrong update to all nodes (akin to a false rumor believed by everyone). There is typically no built-in correction unless a subsequent true update overrides it. Finally, there is the issue of resource exhaustion: although each gossip step is small, an improperly tuned gossip (too high frequency or too large fan-out) can flood the network (“gossip storm”). Modern implementations include rate limits to prevent this, but if they fail, the system might degrade similarly to a broadcast storm. In summary, gossip protocols excel under moderate asynchrony and benign failures, but they can break down under partition, overload, or adversarial conditions that violate their assumptions.

2.3 Community Notes (Platform Governance Case)

Actors / Roles: In Twitter’s Community Notes system, the primary actors are the Contributors – users who are enrolled in the program to write and rate notes. These contributors play a dual role: as note authors, they create explanatory notes on tweets (Posts) that they believe need context or correction; and as note raters, they provide feedback on others’ notes by rating them “Helpful”, “Somewhat Helpful”, or “Not Helpful”[39]. All Contributors are volunteers (platform users) but must meet certain criteria to participate (see Admission Rules). Another implicit actor is the tweet (Post) author whose content is being annotated – they are analogous to the gossip “subject,” though they do not directly partake in the note-writing process. The platform itself (Twitter/X’s Community Notes algorithm and moderators) can be seen as an arbiter role that ultimately decides which notes are displayed, based on the aggregate ratings. However, this decision is algorithmic and community-driven; there isn’t a single editor but rather a ranking algorithm that computes note status from the crowd input[18]. We can also consider the general audience on the platform as a passive actor – they see the publicly shown “Helpful” notes and their behavior (liking, sharing the tweet) may change as a result[40][41]. To summarize, Community Notes actors include: Contributors (writers/raters) as the distributed judges, the Content (tweets) as subjects of evaluation, and the Note ranking system as the procedural authority that elevates certain contributions to visible status.

Message Format: The messages in this protocol are the Notes and Ratings themselves. A Community Note is a structured content item attached to a specific tweet. It typically consists of a short textual explanation or fact-check, often with cited sources or evidence, written in a neutral tone. The note format is standardized – it addresses a claim in the tweet and provides clarifying context or correction. Each note also carries meta-data (author ID, timestamp, etc.) and an evolving score determined by ratings. Ratings are essentially votes from other Contributors: they mark a note as helpful, somewhat helpful, or not helpful. These ratings are input to the note ranking algorithm, which computes an overall helpfulness score. The algorithm notably uses a bridging-based rule: it analyzes the pattern of ratings across different kinds of contributors (for example, across the political spectrum)[19]. A note is only considered Helpful if it receives enough positive ratings from contributors with divergent viewpoints[42][19]. This means the ratings message is not just a simple majority vote; it’s evaluated in a weighted manner to ensure broad agreement. In practice, the message-passing in Community Notes occurs through the platform’s interface: when a contributor submits a note, that note enters a queue (“Needs more ratings” state) visible to other contributors, who then submit rating inputs (each rating is like a small message indicating one user’s opinion on that note). If the note reaches the threshold for diverse helpful votes, the system flips its status to “Helpful” and the note becomes publicly visible under the tweet[18]. Thus, the content moderation protocol here involves two message types: Note proposals and Note ratings, both structured and logged by the platform. No direct peer-to-peer messaging occurs; rather, the platform aggregates these inputs centrally. But logically, it’s a distributed discussion where each contributor’s rating is akin to a “gossip” about the note’s quality, and the final displayed note is the one that survives communal scrutiny.

Admission Rules: Not every Twitter user can become a Community Notes contributor; there are formal admission rules designed to ensure participants are established and potentially trustworthy users. As of launch, to be admitted as a Contributor, a user had to have an account at least 6 months old, a verified phone number, and a history of no recent Twitter rule violations[43]. These criteria function as a Sybil-resistance and quality filter – they reduce the likelihood that brand new or spam accounts can flood the system. Additionally, new Contributors cannot immediately start writing their own notes. They are first required to rate a number of existing notes and build up a positive Rating Impact score[44]. Only after reaching a certain threshold of agreement with others’ consensus (demonstrating they rate notes similarly to the community’s eventual decisions) can they begin to author notes[45]. This staged admission process ensures that new entrants understand the norms of helpful notes before contributing their own. There is also an ongoing governance of participation: contributors who continually write notes that are rated not helpful, or whose ratings often disagree with the eventual outcomes, will see their impact scores drop, potentially losing the ability to write notes. The platform can remove or suspend Contributors who abuse the system (though done sparingly, as the system tries to be community-driven). In summary, admission in Community Notes is gated by reputation and experience: one must prove oneself as a reliable rater over time to gain full participation rights. These rules help maintain a baseline quality and trustworthiness in the contributor pool.

Incentives: Community Notes is designed with a mix of altruistic and gamified incentives for contributors. On one hand, the explicit incentive is the impact score system: contributors earn a higher Writing Impact if their authored notes are frequently rated helpful (which can be a point of pride or status), and a Rating Impact that rises when they rate in alignment with the eventual consensus[44]. These impact scores provide feedback and a form of reputation within the Community Notes system – high-scoring contributors might be informally respected and are officially considered “Top Contributors” who may be called upon to draft notes for popular requests[46]. On the other hand, much of the incentive is intrinsic or social. Contributors are motivated by a sense of mission – the chance to correct misinformation and help other users see accurate context. There is a community ethos that successful notes “add value” to the platform’s discourse. Unlike typical social media, Community Notes contributors receive no public credit on the notes (notes are shown without the author’s handle to keep it impartial), so the reward is largely internal satisfaction or peer recognition within the contributor community. The platform also hints at competition: contributors know that only notes with high helpfulness will be published, so there is incentive to write well-sourced, clear notes that can win broad approval. The bridging algorithm incentivizes writing notes that appeal across ideological lines, since a partisan note is unlikely to ever be rated helpful by the diverse crowd[19]. Thus, contributors are encouraged to find consensus truth rather than score political points. In terms of negative incentives, if someone consistently provides bad input (poor notes or bad-faith ratings), their influence diminishes (low impact scores, perhaps eventual removal). In short, the incentive structure mixes reputation gain, peer esteem, and pro-social fulfillment to encourage high-quality, consensus-oriented contributions to the gossip network of fact-checking.

State Transitions: The Community Notes system maintains several pieces of state that undergo transitions. The primary state is the status of each Note. When a note is first written, its state is “Needs More Ratings” (only visible to other contributors). As ratings come in, an algorithm continuously evaluates whether the note has met the criteria for being considered Helpful. If it meets the threshold – notably requiring a sufficient number of helpful votes from contributors of differing viewpoints – the note’s state transitions to “Helpful”[42]. At that moment, the note becomes publicly visible to all users under the tweet (i.e., it is effectively published)[18]. If instead the note accumulates enough Not Helpful feedback or fails to gather the necessary diverse support, it may be marked “Not Helpful” (or simply remain unrated and never show). Notes can thus be seen as going through a lifecycle: Proposed -> Needs ratings -> Helpful or Not Helpful (finalized). Contributor accounts also have state transitions: new contributors start with limited capabilities, then transition to “fully qualified” status once they pass the rating threshold[45]. Their impact scores fluctuate as they participate – a form of state that reflects their current standing in the community. In the broader sense, the platform’s knowledge base transitions with each successful note: a piece of content on Twitter goes from uncontextualized to contextualized once a note is attached, altering how that content is perceived and engaged with (tweets with notes get fewer likes and shares on average, indicating a shift in the network’s state of misinformation vs understanding[40][41]). One can also consider the collective consensus state: initially there is disagreement or uncertainty about a tweet’s validity; through the note process the community might transition to a shared agreement that “this claim is misleading for reasons X” (embodied in the published note). Technically, if a note’s status were to be re-evaluated (say more ratings come in after it’s marked helpful), it could in theory transition again (though typically once published it stays unless removed by moderation). In summary, Community Notes manages a dynamic state machine where notes and contributors move through qualitative status changes based on ongoing inputs, reflecting the evolving consensus of the community.

Error Handling: Community Notes incorporates measures to handle errors and prevent bad information from being elevated. First, the diversity requirement (bridging algorithm) is a preventative error-handling mechanism: it filters out notes that only one partisan cohort finds helpful, on the assumption that such notes might be biased or misleading to the other side[19]. This reduces the risk of a coordinated faction pushing an incorrect note to visibility. Second, the rating impact system quickly dampens the influence of outlier contributors – if a person consistently rates notes in ways that do not match eventual outcomes (possibly because they misunderstand or deliberately misrate), their ratings carry less weight over time[44]. This is akin to down-weighting “noisy” or malicious nodes in an algorithm, thereby protecting the system from persistent error introduction by a single user. Third, Community Notes allows (indeed relies on) multiple raters and writers, introducing redundancy: many eyes review each note, increasing the chance that errors or low-quality notes are caught by someone. If a note contains a factual error or irrelevant content, ideally enough contributors will rate it Not Helpful, preventing it from ever going public. In cases where a note with errors does slip through and is published, Twitter staff or the community can intervene by adding a better note or, in rare cases, removing a misleading note. The system’s open-source nature means external experts can also audit the algorithm for biases or bugs[47]. Official studies have noted substantial agreement between Community Notes outcomes and professional fact-checkers[48], suggesting the error rate for published notes is low. Nonetheless, error handling is not perfect: a slow or insufficient rating response is a kind of failure to handle a bad note (it might linger in “Needs more ratings” or not get enough attention to be correctly flagged). The system addresses this by prompting more ratings on notes that hover without resolution. In summary, Community Notes handles errors through algorithmic safeguards (bridging, reputation weighting) and by leveraging the wisdom-of-crowds – assuming that blatant mistakes will be voted down before doing harm. The iterative rating process itself is the error correction: notes that are inadequate simply do not graduate to “Helpful” status, functioning as a built-in quality control loop.

Failure Modes: Community Notes can fail or be undermined under several conditions. A primary concern is coordinated adversarial behavior: if a large group of Contributors shares an agenda to push misleading notes, they might attempt to game the diversity requirement by fielding allies in opposing groups to give just enough cross-group support. The system could be captured if the majority of contributors or a savvy coalition collude, especially if they manage to recruit contributors across the opinion spectrum to rubber-stamp certain narratives. This is related to another failure mode: susceptibility to brigading. Although each contributor has one vote per note, external organization (e.g. off-platform forums directing members to join and influence Community Notes) could flood the system with biased contributors. The admission rules (6-month account, etc.) slow this, but a determined campaign could still occur over time. Another failure mode is epistemic fragmentation – when the user base is so polarized that no note can achieve the required diverse consensus, even on clearly false information. In such a scenario, helpful notes might never reach publication because one faction will reflexively reject anything that contradicts their narrative. Indeed, researchers have observed that Community Notes often fails to produce a note for highly polarizing content; it operates more slowly and sometimes not at all on the most contentious posts[49][50]. This means misinformation on divisive issues can slip through uncorrected (the system in effect stalls). Latency is a related issue: Community Notes may take on average ~24 hours to attach a note, whereas misinformation can spread virally within hours[49][51]. During this window, the lack of immediate correction is a failure relative to fast-moving falsehoods. Another failure mode is if Contributor participation dwindles – the system needs a critical mass of active, ideologically diverse raters. If users lose interest or trust (for instance, if they perceive the program as biased or ineffective), the quality and coverage of notes will drop. Finally, being an open system, Community Notes is vulnerable to manipulation of context: for instance, if there is no reliable fact-check available for a complex claim, contributors might not reach consensus and could err. In those cases, the system heavily relies on external fact-checking sources[52]; a breakdown in the broader fact-check ecosystem could reduce Community Notes’ effectiveness. In summary, Community Notes remains stable and effective under conditions of broad good-faith participation and cross-partisan agreement on basic facts; it breaks down or lags when faced with organized manipulation, extreme polarization, or scaling challenges in speed and participation[49][50].

3. Case Environments

3.1 Village Gossip Environment

Latency Tolerance: Village gossip operates on human social time scales – it is tolerant of relatively high latency in information spread. News can take hours, days, or even weeks to circulate through all members of a community, and this is generally acceptable. There is rarely an expectation of instant propagation; what matters is that important information eventually reaches the relevant ears. The gossip network can be fast in a small, tight community (a rumor might go around by the end of the day through face-to-face chats), but it can also be deliberately slow – people might wait for private moments to share tidbits. This environment tolerates delay because human reactions and sanctions do not need split-second updates. In fact, sometimes a slow burn can lend gossip more effect (e.g. a scandal gradually coming to everyone’s knowledge). Of course, certain urgent gossip (warnings of danger or imminent events) may spread more rapidly, but generally the system is content with eventual dissemination. There is also tolerance for latency in verification; a rumor might hang in the air unconfirmed for some time. In short, the village gossip environment is asynchronous and can absorb significant delays without failing – immediacy is less critical than reach.

Norm Authority (Convergence Guarantees): The “authority” of norms in gossip is informal but powerful. Gossip does not guarantee a mathematically provable convergence like a consensus algorithm, but it tends toward a social convergence: eventually most community members arrive at a shared understanding or dominant narrative about the subject. The authority behind this convergence is the community’s collective values and the persistent reinforcement through repeated gossip. Over time, as the story circulates and people observe each other’s reactions, a conventional wisdom emerges (“everyone says that so-and-so was in the wrong”). Gossip’s norm authority is seen in how it can solidify what behavior is regarded as acceptable or not – essentially establishing community verdicts. However, this authority is implicit: there is no single arbitrator, just the weight of majority opinion. In anthropological terms, gossip acts as a normative regulator whose power comes from social approval or disapproval[25]. Its convergence on a stance is not guaranteed – occasionally communities remain split on a rumor’s truth – but often repeated discussion yields a broadly accepted version (sometimes even if inaccurate). We can say gossip provides eventual social consistency: given enough churn, either consensus forms or at least the possible interpretations narrow. The community’s memory then enforces that consensus as the “official unofficial” account. Authority in gossip is thus peer-enforced normativity: if nearly everyone believes a gossip and acts on it (shunning someone, for example), that effectively has the force of rule, even absent formal proof.

Memory Persistence: The persistence of memory in a village gossip system is predominantly human memory and oral tradition. Important pieces of gossip can persist for a very long time in collective memory – notable scandals become part of local lore, retold across generations (a form of persistence). However, details may fade or mutate as they are retold; there is no exact archival record unless someone writes it down (which traditionally they wouldn’t, gossip being unofficial). So the memory is persistent but malleable. Each individual remembers some portion of the gossip they’ve heard, and through periodic retellings, the community reinforces memory. There’s also a notion of “context memory”: past gossip can be resurrected when triggered by new events (e.g., “This reminds me of the time years ago when X did Y…”). Gossip networks have redundant storage – multiple people store the information, which increases durability. If one person forgets, another might recall. On the flip side, false or minor gossip might not persist and can be forgotten if it doesn’t continually circulate or if superseded by new narratives. Culturally, certain forms of gossip (like proverbs or cautionary tales) even get institutionalized, further extending memory. In sum, the environment provides a soft persistence: social memory can last indefinitely especially for high-impact events, but there’s no guarantee of fidelity or completeness over time. The lack of a written log means persistence is a function of continued interpersonal transmission.

Adversarial Assumptions: The village gossip environment usually assumes a baseline of semi-cooperative behavior: while individuals may have personal motives, it’s expected that most gossip is shared in a relatable, if biased, way rather than with cryptographic precision. The system is not hardened against adversaries – a malicious actor can certainly introduce false gossip. The checks on that adversary are social: their credibility can be challenged by others or they might face retaliation if found lying. But structurally, gossip has no built-in immunity to false or malicious input. It assumes that outright fabrications are relatively rare or will be caught by someone’s knowledge. When multiple individuals collude (a coordinated attack in modern terms) to spread the same false story, gossip networks can be quite vulnerable – with enough repetition from different mouths, a falsehood gains credibility (“everybody is saying it”). Historically, this is how smear campaigns or scapegoating operates. Thus, the adversarial model is weak: gossip functions in an environment where trust and shared norms are expected, and it can degrade rapidly if bad actors exploit it. For example, an outsider spreading disinformation in a community that doesn’t know them might be dismissed, but if they pose as an insider or recruit insiders, the gossip channels can be hijacked. Additionally, anonymity is limited in a small village; gossip assumes people know sources implicitly. If information came from an unknown or untraceable source (anonymous letter, etc.), traditional gossip systems find that suspicious or hard to integrate. So gossip works best when everyone can gauge each other’s trustworthiness and there is a shared context; it is not robust against concerted deception beyond those social self-correcting mechanisms.

Collapse Conditions: Gossip networks in a community can collapse or lose effectiveness under certain conditions. One collapse scenario is extreme loss of trust – if people stop believing what they hear from anyone, the gossip circuit breaks down (everyone dismisses talk as “just rumors”). This might happen after multiple incidents of revealed false gossip or if a powerful authority consistently contradicts and punishes informal talk (driving it completely underground). Another collapse condition is when the social network itself disintegrates: if the community fractures (due to conflict, migration, etc.), the web of daily interactions that gossip relies on is gone. Without regular contact or a sense of community, gossip cannot propagate or hold weight. Also, if a community becomes too large or too heterogeneous, gossip may fail to scale – people don’t know each other well enough to care about personal rumors, or they have too many degrees of remove so that the intimacy and trust that fuel gossip wane. In such cases gossip might persist only in smaller subgroups and cease to function community-wide. High levels of fear or surveillance can also dampen gossip to a collapse: for instance, under an oppressive regime or in a climate of mistrust, individuals may avoid gossiping because the risks outweigh the social rewards. Additionally, the advent of alternative information channels (like mass media or digital communications) in a once-isolated village can partially collapse the traditional gossip network by shifting attention elsewhere. Finally, if gossip consistently fails to produce justice or shared understanding – e.g. if lies frequently win and no one can ever be sure of anything – people may disengage, effectively collapsing the utility of gossip. Thus, gossip remains stable when reinforced by trust and community cohesion, but it collapses in environments of pervasive fear, distrust, fragmentation, or competing communication systems.

Participation Incentives: Participation in village gossip is incentivized by the fundamental social nature of humans. People engage in gossip for social bonding, to feel included and knowledgeable within their circle[26]. The fear of social isolation incentivizes listening to gossip (so as not to be out of the loop), and the desire for social capital incentivizes contributing gossip (having interesting news to share grants status). There’s also a protective incentive: being part of the gossip circuit means you get early warnings about threats (like “don’t do business with so-and-so, they cheated someone”) – this practical value motivates participation. Culturally, gossip can be entertaining (the enjoyment of story and drama), which is a direct incentive to participate for leisure. At a normative level, community members may feel a duty to gossip in the sense of keeping their social world under observation – by talking about misdeeds or notable events, they collectively uphold norms (with the incentive of a well-regulated community as the outcome). On the flip side, there are mild disincentives (one doesn’t want to be seen as a gossip who talks maliciously). But gossip participation is usually done within accepted bounds, so it doesn’t taint one’s reputation unless they overdo it or betray confidences. Because gossip often occurs in tight clusters of trust (friends, family), another incentive is reciprocity: you share with me, I’ll share with you. Not participating at all might mark someone as aloof or untrusting. In summary, the incentives are largely social: belonging, information advantage, influence, and recreation. These ensure that gossip is a self-perpetuating activity in any community where people interact regularly.

3.2 Technical Gossip Protocol Environment

Latency Tolerance: Gossip protocols in distributed systems are generally designed for eventual consistency rather than immediate synchronization, which means they tolerate moderate latency in information propagation. The environment acknowledges that it may take multiple gossip cycles for an update to reach all nodes. For example, if each node gossips to one random peer per second, the epidemic spread will cover the network in O(log N) rounds with high probability[53]. This could be seconds or minutes depending on network size and gossip frequency. System designers find this acceptable for many use cases (membership updates, cluster state) where a few seconds delay is not harmful. Gossip protocols trade perfect timeliness for robustness – they are content with slightly stale data as long as it eventually converges. In terms of tolerance, these protocols often allow tuning of the gossip interval: higher frequency for lower latency at cost of bandwidth, or lower frequency to reduce load. The typical environment is one where network latency is non-zero (tens of milliseconds) and node processing takes time, so immediate global broadcast is costly; gossip’s incremental spread is appropriate. There are also time-out based latencies built in (e.g. failure detectors might only declare a node dead after a couple of gossip rounds/timeouts). So the system tolerates that a dead node might not be recognized for a small interval. Overall, the gossip environment favors asynchronous, distributed timing – no global clock or lockstep updates, just eventually all nodes catch up. This tolerance makes gossip well-suited for large, geographically distributed systems where expecting instant consistency is unrealistic. However, gossip is usually not used where very low latency absolute guarantees are required (like high-frequency trading or real-time control systems) – those environments are not a good fit due to gossip’s probabilistic delay.

Norm Authority (Convergence Guarantees): In a distributed protocol context, “norm authority” translates to the guarantee of convergence or consistency in the algorithm. Gossip protocols typically provide probabilistic convergence guarantees. There isn’t an external authority enforcing a single truth; instead, the algorithm’s design ensures that if all nodes follow the protocol, the system will almost surely reach a consistent state (given no further updates). The authority here is the protocol logic and mathematics – e.g. the epidemic theory that shows information will spread to all nodes with high probability[13]. Each node independently applies rules (like “always accept the latest timestamp value” or “mark node failed after k failed pings”) that collectively lead to eventual agreement. There is no central clock or judge to resolve conflicts; thus gossip operates in a weakly consistent environment. For example, if two conflicting updates start, gossip alone doesn’t choose one; typically an application-level rule (last write wins, etc.) must serve as the norm. One can say the “norm” in gossip protocols is consistency through redundancy: the sheer number of exchanges ensures that correct information saturates the network, outweighing any one node’s mistake. The environment assumption is that a majority of nodes are correct and will promulgate correct data, hence convergence to correct state. If that assumption holds, gossip is authoritative in the sense that eventually every node will hold the same view (e.g. same set of members in cluster)[54]. In summary, the convergence guarantee is statistical rather than absolute, but proven to be highly reliable in practical scale systems. The trust model is that each node trusts the algorithm and the information passed by peers (unless augmented with security layers). So the “norm authority” in technical gossip is decentralized consensus enforced by algorithmic rules, rather than a person or a central server.

Memory Persistence: In a distributed gossip environment, state persistence depends on the system’s implementation. Generally, each node holds part or all of the relevant state in memory (RAM) and possibly on disk. For instance, a gossip-based database will keep data permanently in storage while gossiping newer writes, whereas a pure membership service might keep everything in memory with periodic checkpoints. The persistence can be characterized as distributed redundancy: because many nodes will hear about an update, the information is stored in multiple places. This provides fault-tolerance; even if some nodes reboot or lose data, others can re-gossip it back to them when they rejoin (assuming some stable storage of membership). Memberlist-style gossip typically doesn’t write the whole membership list to disk every time, but it could reconstruct it by contacting a seed node if needed. In terms of memory model, gossip protocols often assume an unbounded lifespan of nodes for the duration of interest – i.e., they rely on alive nodes remembering what they’ve seen and propagating it until all have it. If all nodes holding a piece of info go down simultaneously, that info is lost (unless external persistence exists). For example, if a data update is only in volatile memory and the few nodes that got it crashed, the update doesn’t magically survive. Thus, many systems augment gossip with persistent storage (like each update is also logged) to avoid that scenario. In summary, the environment offers high persistence through replication – once an update has spread, it effectively lives in multiple memory locations across the network, making it hard to eradicate (similar to how a rumor, once spread widely, is hard to suppress). But ephemeral states (like a transient error report) may only live as long as nodes keep gossiping it; such state might have a TTL (time to live) after which it’s forgotten if not refreshed. The persistence is configurable: some gossip data is periodically purged (old health-checks, etc.), whereas critical data is kept. The assumption is that even without central storage, the network of nodes collectively provides a durable information substrate as long as enough nodes remain.

Adversarial Assumptions: Classic gossip protocols assume a non-adversarial (benign) failure model: nodes may crash or messages may be dropped, but nodes do not intentionally lie or collude to mislead. Under this assumption, gossip works very well – any incorrect information is due to transient error and fades out, while correct information eventually prevails via consistent repetition. However, if we introduce adversaries (Byzantine behavior), the gossip environment becomes much trickier. A malicious node could emit bogus state (e.g., claim “Node B is down” when it isn’t, or introduce a fake transaction). Without authentication or trust mechanisms, honest nodes will treat that misinformation equally and propagate it. The environment of many gossip deployments (like internal data centers) is controlled and thus assumes trust. If used in open environments (like peer-to-peer overlays on the internet), additional layers (cryptographic signatures, majority voting) might be needed to mitigate adversaries. Some gossip variants exist for Byzantine scenarios, but they are more complex and less common. In summary, the baseline adversarial assumption for gossip is fail-stop faults, not Byzantine. The protocol tolerates a certain fraction of nodes being unresponsive (crashed) or slow, but not a significant fraction actively corrupting data. If an adversary controls a minority of nodes, the redundancy of gossip might dilute their impact (honest nodes keep sharing correct info too), but if they control enough or if they can sybil-attack (present many fake nodes), they can inject or suppress updates arbitrarily. Therefore, the environment needs either inherent trust or external trust enforcement (e.g., all updates are cryptographically signed by a legitimate source). The summary: gossip thrives in cooperative, open environments of partial trust; it is not inherently secure against coordinated malicious actors and typically assumes none are present or that their influence is outweighed by honest participants.

Collapse Conditions: A technical gossip system can experience collapse or severe degradation under several conditions. One is a network partition or sustained communication failure: if nodes cannot reach each other due to network issues, gossip cannot fulfill its role. In a full partition, the protocol essentially forks (each partition gossips among itself diverging state). If the partition remains, the global consistency goal collapses. Another collapse condition is overload – if the gossip parameters are mis-tuned such that message volume exceeds what the network can handle, it can lead to congestive collapse (messages get dropped, causing retries or more messages, further worsening congestion). This scenario might occur if gossip fan-out or frequency is set too high for a large N, turning robust epidemic spread into a broadcast storm. A related condition is extremely high churn (nodes constantly joining/leaving multiple per second); the protocol may not converge because membership changes outpace dissemination, leading to confusion or stale info (e.g., by the time “X failed” has reached everyone, X might have rejoined and someone else left). Gossip protocols can also collapse if resource limits on nodes are hit: e.g., if state grows large (like tens of thousands of updates buffered) and nodes run out of memory or bandwidth, they might drop out, causing further disruption. In general, gossip’s resilience means partial failures are tolerated (it degrades gracefully as more messages are lost or nodes fail), but beyond a threshold, the feedback loop breaks down – if too few nodes are functioning or the loss rate is too high, information never reaches quorum and consistency is never achieved. Unlike a centrally coordinated system, gossip has no global fail-safe; if chaos exceeds a limit, it doesn’t converge at all (all nodes might end up with divergent views). This point of collapse is usually well beyond normal operating conditions, but possible in worst-case adversarial or disaster scenarios. Finally, a context failure can occur if the environment fundamentally changes (like network topology radically shifting faster than gossip can adapt, or nodes suddenly need to gossip a type of data they weren’t programmed for), essentially invalidating the protocol’s assumptions. In short, gossip protocols break down under extreme network failures, overload, or churn where their probabilistic guarantees can no longer catch up, and they lack a central authority to restore order.

Participation Incentives: In automated systems, “participation” is built-in (nodes run the protocol by design), so the incentive is not a human factor but a system requirement. Each node “participates” because it’s running software that does so, otherwise it wouldn’t function in the cluster. However, we can think in terms of rational nodes (like in game-theoretic or decentralized P2P networks): the incentive to follow the gossip protocol is that it yields mutual benefits – the node gains knowledge of the overall system (membership, latest data) which it needs to do its job correctly. For example, a caching server will participate in gossip to know which peers have which content or who is alive, enabling it to route requests properly. If it opted out, it would soon have stale or missing information and perform poorly or be ejected by others. In more voluntary networks (like peer-to-peer file sharing using gossip to spread index information), the incentive might be enforced by protocol rules (you only get updates if you also share updates). In essence, gossip aligns with self-interest in a cooperative sense: every node wants the system to be consistent (for correctness) and robust (so it can still operate if others fail), and gossip provides that with minimal overhead per node[33][34]. There is also often a simplicity incentive – gossip algorithms are simple to implement and maintain compared to complex synchronized algorithms, which appeals to system designers and by extension the nodes run simpler code (less chance of bugs that would hurt the node). In blockchain or DAO contexts (if gossip used there), nodes might have explicit rewards for relaying information (like Bitcoin nodes gossip transactions for indirect reward of network health and maybe transaction fees). But in classical cases like Cassandra or Consul, the incentive is inherent: a node that doesn’t gossip effectively isolates itself. Therefore, the environment assumes nodes will adhere to the protocol because it’s effectively part of their function and interest to do so. Deviating (like refusing to forward messages) has no benefit to a node because it doesn’t conserve significant resources and only harms the node’s knowledge. Thus, gossip protocols are designed to be incentive-compatible in cooperative scenarios – what’s good for the network (sharing updates) is good for each node too (getting updates)[55][56].

3.3 Community Notes Environment

Latency Tolerance: Community Notes operates within a social media ecosystem where content virality is measured in minutes or hours. However, the process it uses is relatively slow and deliberative. The system tolerates significant latency in reaching a decision about a note’s helpfulness – often on the order of many hours to a day for a note to accumulate enough ratings and be displayed[49][51]. This means the environment accepts that misinformation might not be immediately corrected by a note; the trade-off is that a higher-confidence, community-vetted note appears later. Empirical analysis confirms this lag: the average time for a Community Note to be appended to a misleading post is around 24 hours, whereas simpler crowdsourced replies (“snoping”) can appear within 2 hours[49][51]. The platform thus implicitly tolerates that its community-driven approach is slower than automated or dedicated fact-checker responses. There is some built-in urgency mechanisms (e.g. popular tweets get more contributor attention, and users can “request a note” which alerts top contributors[46]), but it’s still not real-time. The rationale is likely that notes need a diverse consensus, which requires waiting for enough ratings from different time zones and perspectives. The environment is one of rapid information spread but slow correction – not ideal, but the system is predicated on the idea that a slightly delayed but broadly legitimate note is better than a hasty or contentious one. If extreme rapid response is needed, Community Notes is not currently optimized for that; it assumes issues can wait for the crowd to weigh in. This tolerance has limits: if notes took weeks, they’d be moot. So the platform provides analytics and notifications to encourage quicker turnaround (e.g., notifying contributors of notes needing ratings). In summary, Community Notes’ environment accepts latency as a cost for accuracy and consensus, functioning on a human-moderation timescale rather than algorithmic instantaneity.

Norm Authority (Convergence Guarantees): In Community Notes, norm authority manifests as the platform’s algorithms and guidelines that determine when consensus is reached on a note. The ultimate authority is the note ranking algorithm which applies the “bridging” rule requiring cross-group agreement[42][19]. This algorithm is effectively the judge that decides a note’s status. It encodes the norm that only broadly agreed notes are considered helpful (which acts as a convergence criteria). The environment assumes that truth or helpful context often lies in that intersection of agreement between differing viewpoints. In practice, this yields a kind of convergence guarantee with diversity constraint: a note converges to Helpful only if both sides converge on it being good. If only one side of contributors ever supports it, the system deliberately withholds convergence (note remains Needs More Ratings or Not Helpful). Thus, the norm authority here is explicitly programmed to prevent one-sided convergence. The Community Notes guidelines also serve as normative authority: contributors are guided to provide certain types of notes (e.g., those with factual evidence, not opinion) and the community typically converges to those norms over time – evidenced by alignment with professional fact-checkers in many cases[48]. However, unlike a strict protocol with guaranteed termination, Community Notes does not guarantee convergence on every piece of content. In some cases, no note will ever get broad approval, effectively meaning the system fails to converge for that content. The platform is okay with that outcome (no note shown) rather than forcing a contested note through. So the governance norm is conservative: better to have no consensus note than a partisan note. This implies the “authority” resides in community consensus itself – if consensus can’t be reached, the system abstains from acting. On content where consensus is reachable, the eventual authority is strong: a displayed Community Note carries weight as a collectively endorsed correction. In summary, Community Notes relies on algorithmically mediated consensus as its norm authority, with the platform’s code deciding when the bar is met. It ensures a kind of credible neutrality: the note is authoritative precisely because it met stringent, transparent criteria of multi-party approval, rather than because the company said so. The convergence, when it occurs, is thus backed by the legitimacy of crowd agreement.

Memory Persistence: The Community Notes system maintains a persistent record of notes and contributor reputations. All notes that are written (including those that never become public) are stored in the system’s databases. This provides a lasting memory: a note that was rated not helpful remains in the data (for auditing or future analysis), and notes that do become helpful persist as annotations on the tweet even if the tweet continues circulating. In fact, once attached, a Helpful note will stay visible under that tweet for as long as the tweet exists on the platform, effectively becoming part of the content’s history. Contributor impact scores are also persistent, accumulating over a user’s participation tenure. The open-source nature of Community Notes means data on notes and ratings is archived and available to the public, enhancing persistence[47]. In terms of information propagation, a note’s content is persistent in that any user who sees the tweet later will also see the note (if it was marked helpful), regardless of whether they were around when it was first written. This is unlike ephemeral gossip – here the system actively shows the note to any viewer of the tweet, ensuring the context isn’t lost. There is also persistent learning: the algorithm’s calibration (what constitutes diverse agreement) can be updated based on past performance, and contributors carry forward their reputations. One area where persistence is intentionally limited is author identity in public view: notes are shown without credit, focusing attention on the content, not the author. But internally, the system remembers who wrote what (for impact scoring and accountability). Another aspect is that Community Notes attaches to specific posts; if a post is deleted, the note is effectively removed from public view too (though remains in the data). Summarily, the environment provides high persistence of the collective knowledge created: it’s logged, open for review, and continuously applied to modulate user experience (notes seen by readers, scores influencing contributor capabilities). It’s a far cry from the transient whisper network of classic gossip – here the gossip (notes) becomes part of the permanent public record once ratified.

Adversarial Assumptions: The Community Notes system anticipates some adversarial behavior and is explicitly designed to mitigate it, though it also assumes a large pool of good-faith participants. The bridging algorithm is a direct response to the threat of partisan brigading – it assumes that without this, people of one ideology might upvote only notes that favor their side, and thus the system demands cross-ideological cooperation to get a result[42]. This is effectively acknowledging an adversarial scenario (partisan bias) and countering it. The admission criteria (older account, verified phone) assume potential adversaries might create fake accounts, so barriers are erected to raise the cost of sybil attacks. Furthermore, the rating impact mechanism assumes some raters might be poor or malicious – by reducing their weight over time, the system is resilient to a small fraction of adversaries. However, Community Notes likely assumes that a majority of active contributors are honest or at least not monolithic in dishonesty. If a coordinated group of bad actors managed to become a large fraction of contributors while maintaining a veneer of diversity, they could in theory game the system. The open design (open-source code and data) means adversaries also can study how to exploit it, which the designers accept as the cost of transparency[47][57]. In essence, the system is robust against casual mischief (one user trying to push a bad note) but not invulnerable to sophisticated collusion. There is a reliance on scale: the hope is that with enough contributors from different backgrounds, it’s hard to secretly coordinate a majority. The platform also retains the final veto; if something egregious slipped through, Twitter/X staff could intervene (an ultimate backstop against adversaries, albeit rarely invoked). So the adversarial model is moderately hostile environment: it expects attempts at manipulation and has mechanisms like diversity-checking, reputation, and entry barriers to handle them[50]. Yet it still fundamentally trusts the wisdom of crowds principle – that collectively, genuine contributors outnumber and outweigh the bad actors. If that trust fails (e.g., a concerted infiltration), the system would likely produce skewed or no outcomes for affected content. Thus Community Notes is an experiment in community resilience: partially fortified but ultimately dependent on the community’s good faith to resist adversarial capture.

Collapse Conditions: Community Notes could collapse or be rendered ineffective under several conditions. One collapse condition is political polarization beyond a functional threshold – if contributors are so polarized that they rarely agree on facts, then the bridging algorithm will frequently result in no notes getting enough diverse support. In that scenario, Community Notes essentially fails to function on the topics where it’s needed most (each side writes notes the other side downvotes, leading to stalemate). Empirical hints of this are seen in cases where many notes are written on a contentious tweet but none become public due to lack of cross-group consensus (a form of systemic paralysis). If this becomes common, the value of the system diminishes and users may disengage, a collapse in utilization. Another collapse condition is majority capture or manipulation: if a well-organized faction (or state-sponsored influence operation, for example) manages to enroll enough Contributors and coordinate their actions, they could start getting biased or false notes approved (by also controlling a token opposition to satisfy bridging). This would undermine the credibility of Community Notes – once users see clearly skewed or false notes, trust is lost. The system’s legitimacy is fragile and could collapse if perceived as hijacked. A more mundane collapse scenario is simply lack of participation: if Twitter’s user base or management doesn’t support Community Notes (e.g., if policies change or it fails to recruit enough active contributors), notes might not be written or rated in sufficient volume. The system could wither away from low activity, especially since it relies on voluntary labor. Also, any major platform shifts (like Twitter’s algorithms hiding Community Notes or the company shutting it down for political reasons) would externally collapse the system. Technically, if the platform got rid of the diversity requirement or lowered standards, it might flood notes everywhere and collapse quality (a different kind of failure). There’s also reliance on factual resources: as noted, many notes reference professional fact-checks or sources[52]. If the broader information ecosystem collapsed (e.g., no reliable sources to cite), Community Notes would struggle to produce convincing context, and conspiracy or rumor might fill the void, which could also ruin the effort. In summary, Community Notes breaks down under extreme polarization, orchestrated manipulation, insufficient community engagement, or loss of credibility. Its design aims to be self-correcting, but those conditions represent stresses beyond which the protocol cannot uphold its mission.